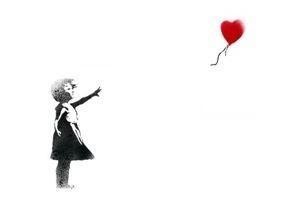

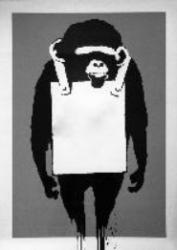

We all (don’t know) who Banksy is: the elusive street artist behind the likes of ‘Balloon Girl’ and ‘Flower Thrower’ (see images below). Banksy is well known for encouraging the use of their works by making high-resolution images publicly available for download, and otherwise making a name for themselves through their anti-authoritarian, anti-capitalist social commentary. Despite having previously stated that ‘copyright is for losers’, Banksy (via their London-based company Pest Control Office Limited [Pest Control]), has recently been engaging with Australia’s Intellectual Property (IP) regimes, filling the following two trade mark applications (Applications) in 2019:

|

No. |

Mark |

No. |

Mark |

|

2025772 |

|

2025771 |

|

Oppositions by Full Colour Black Limited

Despite initially being refused, Pest Control’s Applications were eventually accepted by IP Australia in April 2021. In line with the normal trade mark application process, the Applications were then advertised on the Australian Trade Marks Register, open for opposition by third parties for a two-month period.

During this time, Full Colour Black Limited (Full Colour Black), an international ‘contemporary Art Licensing company’, lodged oppositions against the Applications. Full Colour Black sells greeting cards which incorporate Banksy’s artwork, so the registration of the Trade Marks would limit its ability to commercialise the infamous street art. The Applications have been opposed on a number of grounds available under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Act), being:

|

Section |

Ground |

|

41 |

trade mark not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods and/or services |

|

43 |

trade mark is likely to deceive or cause confusion |

|

58 |

applicant is not the owner of the trade mark |

|

62(b) |

trade mark application accepted on basis of false evidence or representations |

| 62A |

application made in bad faith |

With the opposition yet to progress to a Hearing, it is not entirely clear what arguments Full Colour Black will seek to rely on. However, hypotheses can be drawn from similar proceedings brought by Full Colour Black against Pest Control through the European Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) in 2020 and 2021. Here, Full Colour Black successfully argued that the following registered EU trade marks held by Pest Control should be cancelled on the basis that they were non-distinctive and filed in bad faith:

| No. | Mark | No. |

Mark |

|

018118853 |

|

017981624 |

|

|

017981629 |

|

017981633 |

|

|

017981636 |

|

017981637 |

|

The EUIPO determined that because Pest Control’s marks were otherwise works of public graffiti which were free to be photographed by the general population and disseminated widely, their use was not as a trade mark. More damning for Pest Control was that this finding was supported by Banksy’s own quotes, such as that included in their 2006 book ‘Wall and Piece’:

any advertisement in public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours… to take, rearrange and re-use.

Further criticism from the EUIPO came in relation to the goods and services claimed by each of Pest Control’s applications. Trade marks are applied for and registered in relation to specific goods and services, which are categorised into ‘classes’. For example, most stationary-related goods are categorised into class 16, including: paper, cardboard, and printed mater, such as books, pamphlets and brochures. If a trade mark is not used in relation to its claimed goods and/or services, it may be vulnerable to cancellation for non-use or being filed in bad faith, particularly if it can be shown that the applicant never intended to use the mark in relation to its claimed goods and services, but applied for it anyway in an attempt to prevent others from using it.

Although Banksy had opened a retail store, Gross Domestic Product, in an effort to sell merchandise related to their marks, the EUIPO found the store was ‘inconsistent with honest practices’ and had ‘unfortunately undermined’ Pest Control’s case. Once again, a particularly unhelpful comment was made, this time by a director of Pest Control, to support this finding:

Banksy was not trying to carve out a portion of the commercial market by selling his goods. He was merely trying to fulfil the trade mark class categories…to circumvent the non-use of the sign requirement under EU law.

So, how will the Australian oppositions fare?

It is unclear if either case will be defended by Pest Control, as it has failed to provide any ‘evidence in answer’ to either of Full Colour Black’s oppositions by the relevant deadlines. Although entirely speculative, this shortcoming could have potentially had something to do with the additional ground filed by Full Colour Black under section 58 of the Act, being that ‘the applicant is not the owner of the trade mark‘. This was not considered in the EUIPO proceedings, and it will certainly be interesting to see how (or if) Pest Control attempts to address this at a later stage in the oppositions. Speaking recently to the World Trade Mark Review, Joel Masterson, the Director of By George Legal (Full Colour Black’s legal representation), stated:

We’re basically arguing that the true human owner cannot be verified based on what’s been supplied to IP Australia. And more importantly, that the owner is definitely not the applicant (Pest Control).

‘Authorship’ is a crucial component of Australian IP law, being the starting point for determining who ‘owns’ various IP rights. Under copyright law, unless the author of a work has assigned or licensed their rights away, they will remain the owner of their work. However, in relation to trade mark ownership, a trade mark applicant can be the legitimate owner of their mark despite not being the original creator of the device constituting the application, provided they have acquired ownership (generally by way of sale or transfer) and they have used (or intend to use) the device in trade or commerce.

This is posited as part of the reason why Banksy (through Pest Control) has pursued international trade mark registrations. If Banksy wanted to bring a claim for copyright infringement in relation to one of their works, they would have to verify themselves as the original creator (or legitimate owner) of the works and thus, reveal their identity. However, by applying for trade marks and listing Pest Control as the owner, Pest Control is (at least in theory) entitled to pursue third party traders who may be infringing their marks.

Nonetheless, and as evidenced by Joel Masterson’s comment, Banksy’s pursuit to retain anonymity may have an indirect affect in these proceedings. To avoid any doubt, some trade mark owners will include an endorsement on their registration to confirm that they have consent from the original creator of their device to use it as a trade mark. This is present in the Applications, which each note that ‘BANKSY has consented to use of his/her artwork as a trade mark‘. The legitimacy of this consent is being called into question by Full Colour Black, with Joel Masterson also revealing in the same article that By George Legal have obtained a copy of the trade mark agreement between Banksy and Pest Control which ‘does not identify the party named as Banksy and is signed by the pseudonym in stylised script‘. Full Colour Black therefore ‘believes that the trade mark agreement cannot satisfy IP Australia that the “real” Banksy authorised the filing of the applications’.

The recent decision of Pham Global Pty Ltd v Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd1 also supports Full Colour Black’s position. Here, the sole director of Insight Radiology Pty Ltd (later, Pham Global) filed a trade mark application in their personal capacity. However, the true owner of the mark was the company, Pham Global, not the director in their personal capacity. Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd (Insight Clinical), the owner of a similar logo mark claiming similar services, successfully opposed the registration of the mark. After various appeals, the Full Federal Court found in favour of Insight Clinical. Although a number of grounds were considered, the Court particularly examined the concept of trade mark ownership, determining that:

- trade mark ownership requirements must be satisfied at the time of filing; and

- only the true owner of a trade mark has the right to deal with the mark, and

- as such, trade mark ownership issues cannot be remedied by assignment even if the assignee is the true owner.

The implication for Banksy/Pest Control is that if the Applications were not filed by the true owner in the first instance, the Applications will be defective. As was the case with Pham Global, this cannot be cured by further dealings with the mark, which Banksy and Pest Control appear to have attempted.

Is it back to the drawing board for Banksy?

The Australian oppositions are still very much alive, with a hearing date yet to be set in either case. While it may be tempting to apply the EUIPO proceedings as precedent, the fate of the Applications remain unclear. The high threshold required to successfully oppose a trade mark on the basis of bad faith in Australia does bode well for Banksy/Pest Control, with an opponent being required to demonstrate that a trade mark applicant’s conduct falls ‘short of the standards of acceptable commercial behaviour observed by reasonable and experienced persons‘. Despite Pest Control having the ability to access an appeal de novo under the Act (essentially a chance to re-start the proceedings ‘from scratch’), only one ground of opposition need be successful for a Trade Marks Hearing Officer to determine that Banksy’s trade marks should not proceed to registration.

So, if we were Banksy, we’d be sharpening our pencils. Either way, we will be sure to report back.

This article was written by Luke Dale, Partner, Lauren Clarke, Solicitor and Annabel Bramley, Law Graduate.

1 (2017) 251 FCR 379.